Minds numbed from a day of unrelenting beauty. I knew Samarkand was beautiful, but wasn’t prepared for this.

Samarkand is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central Asia. There is evidence of human activity in the area of the city from the late Paleolithic era, though there is no direct evidence of when exactly Samarkand was founded; some theories propose that it was founded between the 8th and 7th centuries BC. Prospering from its location on the Silk Road between China and the Mediterranean, at times Samarkand was one of the greatest cities of Central Asia.

By the time of the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, it was the capital of the Sogdian satrapy. The city was taken by Alexander the Great in 329 BC, when it was known by its Greek name of Marakanda. The city was ruled by a succession of Iranian and Turkic rulers until the Mongols under Genghis Khan conquered Samarkand in 1220.

The city is noted for being an Islamic centre for scholarly study. In the 14th century it became the capital of the empire of Timur (Tamerlane) and is the site of his mausoleum (the Gur-e Amir). The Bibi-Khanym Mosque (a modern replica) remains one of the city’s most notable landmarks. The Registan was the ancient centre of the city. The city has carefully preserved the traditions of ancient crafts: embroidery, gold embroidery, silk weaving, engraving on copper, ceramics, carving and painting on wood.

Modern-day Samarkand is divided into two parts: the old and new city. The old city includes historical monuments, shops, and old private houses, while the new city includes administrative buildings along with cultural centres and educational institutions.

In 1370 the conqueror Timur (Tamerlane), the founder and ruler of the Timurid Empire, made Samarkand his capital. During the next 35 years, he rebuilt most of the city and populated it with the great artisans and craftsmen from across the empire. Timur gained a reputation as a patron of the arts and Samarkand grew to become the centre of the region of Transoxiana. Timur’s commitment to the arts is evident in the way he was ruthless with his enemies but merciful towards those with special artistic abilities, sparing the lives of artists, craftsmen and architects so that he could bring them to improve and beautify his capital. He was also directly involved in his construction projects and his visions often exceeded the technical abilities of his workers. Furthermore, the city was in a state of constant construction and Timur would often request buildings to be done and redone quickly if he was unsatisfied with the results. Timur made it so that the city could only be reached by roads and also ordered the construction of deep ditches and walls, that would run five miles in circumference, separating the city from the rest of its surrounding neighbours. During this time the city had a population of about 150,000. This great period of reconstruction is encapsulated in the account of Henry III’s ambassador, Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, who was stationed there between 1403 and 1406. During his stay the city was typically in a constant state of construction. “The Mosque which Timur had caused to be built in memory of the mother of his wife…seemed to us the noblest of all those we visited in the city of Samarkand, but no sooner had it been completed than he begun to find fault with its entrance gateway, which he now said was much too low and must forthwith be pulled down.”

Between 1424 and 1429, the great astronomer Ulugh Beg built the Samarkand Observatory. The sextant was 11 metres long and once rose to the top of the surrounding three-storey structure, although it was kept underground to protect it from earthquakes. Calibrated along its length, it was the world’s largest 90-degree quadrant at the time. However, the observatory was destroyed by religious fanatics in 1449.

The Registan was the heart of Samarkand of the Timurid dynasty. The name Rēgistan means “Sandy place” or “desert” in Persian.

The Registan was a public square, where people gathered to hear royal proclamations, heralded by blasts on enormous copper pipes called dzharchis – and a place of public executions. It is framed by three madrasahs (Islamic schools) of distinctive Islamic architecture.

The three madrasahs of the Registan are: the Ulugh Beg Madrasah (1417–1420), the Tilya-Kori Madrasah (1646–1660) and the Sher-Dor Madrasah (1619–1636). Madrasah is an Arabic term meaning school.

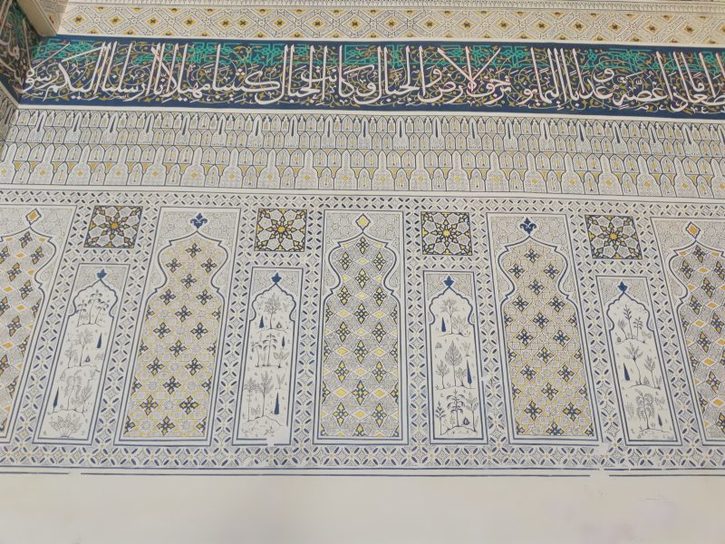

Ulugh Beg Madrasah (1417–1420), built by Ulugh Beg during the Timurid Empire era, has an imposing iwan with a lancet-arch pishtaq or portal facing the square. The corners are flanked by high minarets. The mosaic panel over the iwan’s entrance arch is decorated by geometrical stylized ornaments. The square courtyard includes a mosque and lecture rooms, and is fringed by the dormitory cells in which students lived. There are deep galleries along the axes. Originally the Ulugh Beg Madrasah was a two-storied building with four domed darskhonas (lecture rooms) at the corners.

Sher-Dor Madrasah (1619–1636). In the 17th century the ruler of Samarkand, Yalangtush Bakhodur, ordered the construction of the Sher-Dor and Tillya-Kori madrasahs. The tiger mosaics on the face of each madrassa are interesting, in that they flout the ban in Islam of the depiction of living beings on religious buildings.

Tilya-Kori Madrasah (1646–1660) It was not only a residential college for students, but also played the role of grand masjid (mosque). It has a two-storied main facade and a vast courtyard fringed by dormitory cells, with four galleries along the axes. The mosque building (see picture) is situated in the western section of the courtyard. The main hall of the mosque is abundantly gilded.

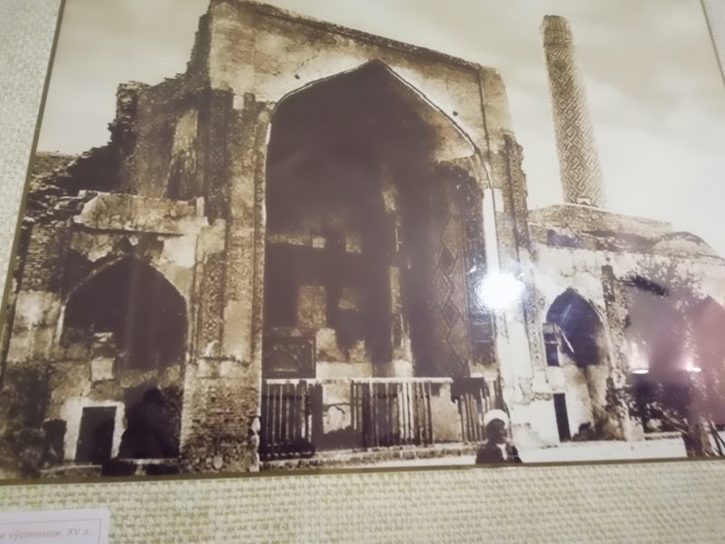

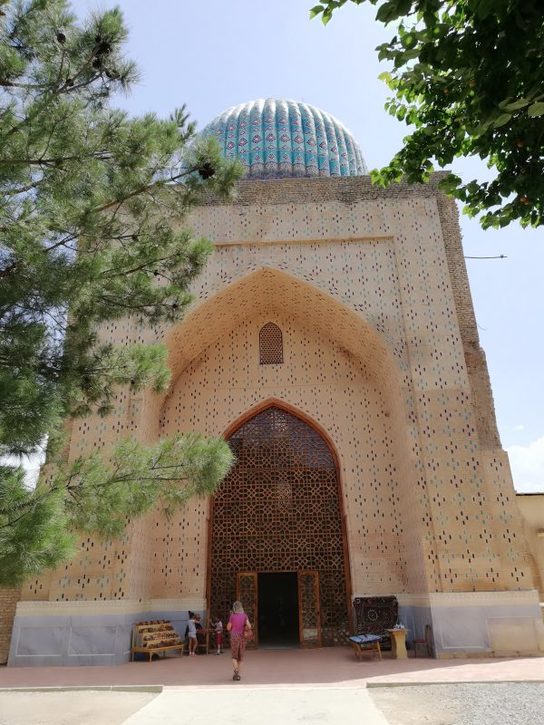

Bibi-Khanym Mosque is one of the most important monuments of Samarkand. In the 15th century it was one of the largest and most magnificent mosques in the Islamic world. By the mid-20th century only a grandiose ruin of it still survived, but now major parts of the mosque have been restored. Bibi-Khanym was Timur’s Chinese-born wife.

After his Indian campaign in 1399 Timur decided to undertake the construction of a gigantic mosque in his new capital, Samarkand. When he returned from his military campaign in 1404 the mosque was almost completed. However, Timur was not happy with the progress of construction, therefore he immediately made various changes, especially concerning the main cupola.

From the beginning of the construction, problems of statistical regularity of the structure revealed themselves. Various reconstructions and reinforcements were undertaken in order to save the mosque. However, after just a few years, the first bricks had begun to fall out of the huge dome over the mihrab.It forced Timur to retaliate often beyond the structural rules. His builders were certainly aware of that, however he didn’t want to accept their opinion and reality.

There is a story that the architect fell madly in love with Timur’s wife and demanded a kiss, otherwise he would refuse to finish the mosque. When Timur returned a mark was still visible on his wife’s face, so he had the architect executed and ordered that married women should wear veils so as not to excite men.

In the late 16th century the Abdullah Khan II (Abdollah Khan Ozbeg) (1533/4-1598), the last Shaybanid Dynasty Khan of Bukhara, cancelled all restoration works in Bibi Khonym Mosque. After that, the mosque came down and became a ruins gnawed at by the wind, weather, and earthquakes. The inner arch of the portal construction collapsed in 1897. During the centuries the ruins were plundered by the inhabitants of Samarkand in search of building material especially the brick of masonry galleries along with the marble columns.

A first basic investigation and securing the ruins was made in Soviet times. Late in the 20th century, the Uzbek government began restoration of three dome buildings and the main portal. In 1974 the government of the then-Uzbek SSR began the complex reconstruction of the mosque.The decoration of domes and facades was extensively restored and supplemented. Work on the mosque restoration continues now.

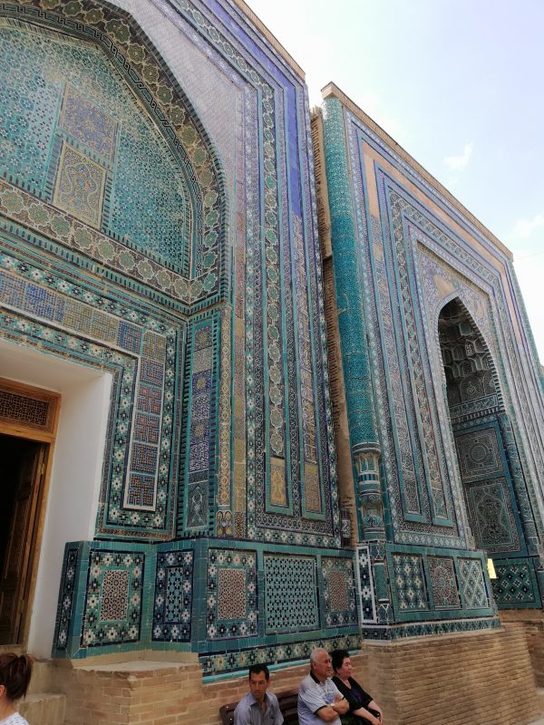

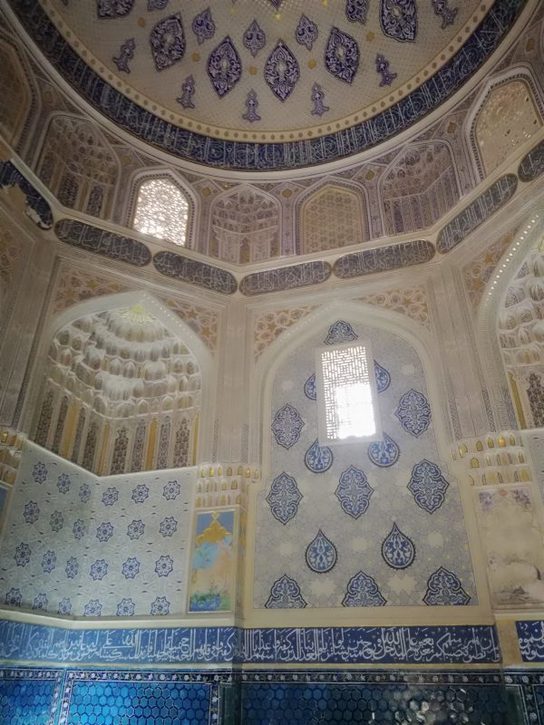

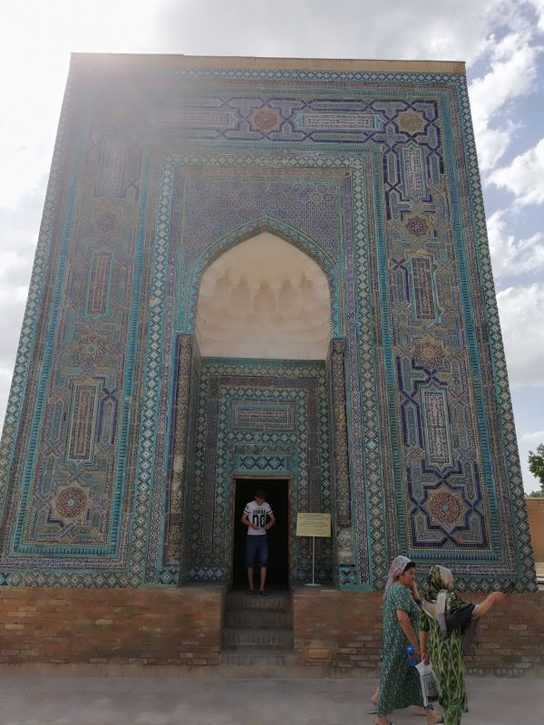

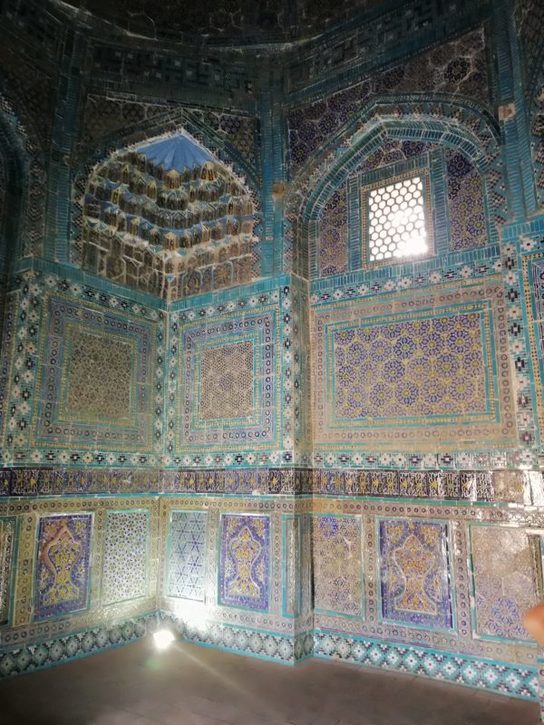

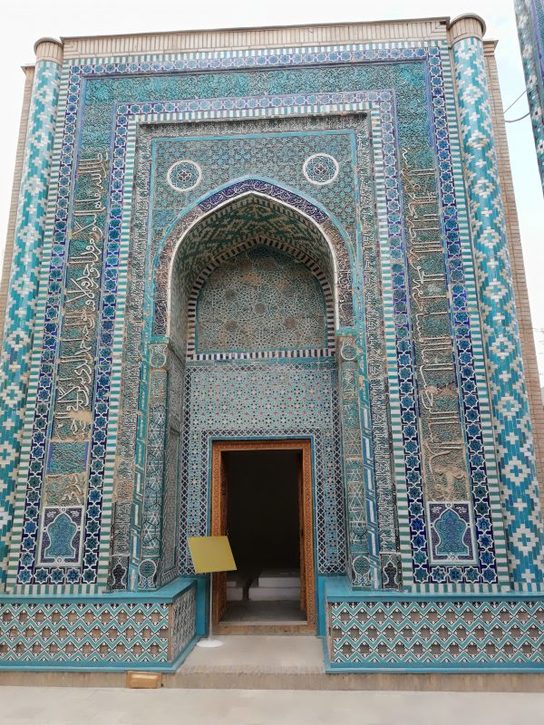

The Shah-i-Zinda Ensemble includes mausoleums and other ritual buildings of 9-14th and 19th centuries. The name Shah-i-Zinda (meaning “The living king”) is connected with the legend that Kusam ibn Abbas, the cousin of the prophet Muhammad was buried there after he came to Samarkand with the Arab invasion in the 7th century to preach Islam. Popular legends speak that he was beheaded for his faith. But he took his head and went into the deep well (Garden of Paradise), where he’s still living now.

The Shah-i-Zinda complex was formed over eight (from 11th till 19th) centuries and now includes more than twenty buildings.

The ensemble comprises three groups of structures: lower, middle and upper connected by four-arched domed passages locally called chartak. The earliest buildings date back to the 11-12th centuries. Mainly their bases and headstones have remained now. The most part dates back to the 14-15th centuries. Reconstructions of the 16-19th centuries were of no significance and did not change the general composition and appearance.

The initial main body – Kusam-ibn-Abbas complex – is situated in the northeastern part of the ensemble. It consists of several buildings. The most ancient of them, the Kusam-ibn-Abbas mausoleum and mosque (16th century), are among them. It is still a working mosque and an imam was singing for people who went to pray while we were there.

The upper group of buildings consists of three mausoleums facing each other. The earliest one is Khodja-Akhmad Mausoleum (1340s), which completes the passage from the north. The Mausoleum of 1361, on the right, restricts the same passage from the east.

The middle group consists of the mausoleums of the last quarter of the 14th century – first half of the 15th century and is concerned with the names of Timur’s relatives, military and clergy aristocracy. On the western side the Mausoleum of Shadi Mulk Aga, the niece of Timur, stands out. This portal-domed one-premise crypt was built in 1372. Opposite is the Mausoleum of Shirin Bika Aga, Timur’s sister.

Next to Shirin-Bika-Aga Mausoleum is the so-called Octahedron, an unusual crypt of the first half of the 15th century.

Near the multi-step staircase the most well proportioned building of the lower group is situated. It is a double-cupola mausoleum of the beginning of the 15th century. This mausoleum is devoted to Kazi Zade Rumi, who was the scientist and astronomer. Therefore the double-cupola mausoleum which was built by Ulugbek above his tomb in 1434-1435 has the height comparable with cupolas of the royal family’s mausoleums.

The main entrance gate to the ensemble (Darvazakhana or the first chartak) turned southward was built in 1434-1435 under Ulugbek.