Went to see the grandiose theatre before setting of for Sarai Batu. We were sorry to leave Astrakhan, a gentle place that moves as slowly as the Volga and with lovely people like motorists that stop for you to cross the road even when there isn’t a pedestrian crossing and strangers who smile and say hello. We ate at the Dacha outdoors restaurant on the Volga Embankment for the last night and the live singer played No Woman No Cry for us.

Sarai (from Persian sarāi, “palace” or “court”) was the name of two cities, which were successively capital cities of the Golden Horde, the Mongol kingdom which ruled much of Central Asia and Eastern Europe, in the 13th and 14th centuries. They were among the largest cities of the medieval world, with a population estimated by the 2005 Britannica at 600,000.

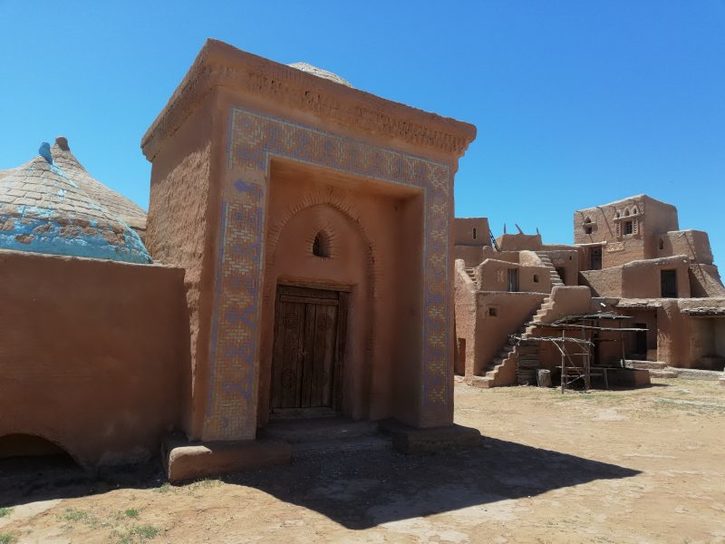

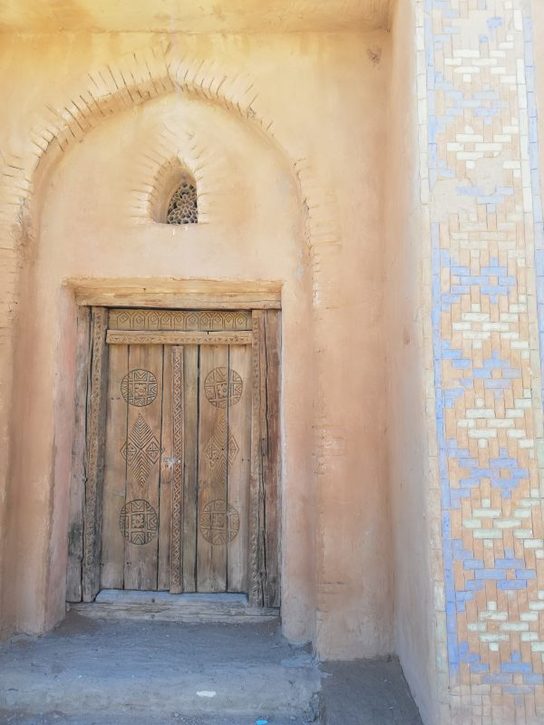

Old Sarai”, or “Sarai Batu” or “Sarai-al-Maqrus” (al-Maqrus is Arabic for “the blessed”) was established by Mongol ruler Batu Khan in the mid-1240s, on a site east of the Akhtuba river, near to the modern village of Selitrennoye.

Sarai was the seat of Batu and his successor Berke. Under them Sarai was the capital of a great empire. The various Rus’princes came to Sarai to pledge allegiance to the Khan and receive his patent of authority (yarlyk).

Sarai was described by the famous traveller Ibn Battuta as “one of the most beautiful cities … full of people, with the beautiful bazaars and wide streets”, and having 13 congregational mosquesalong with “plenty of lesser mosques”. Another contemporary source describes it as “a grand city accommodating markets, baths and religious institutions”. An astrolabe was discovered during escavations at the site and the city was home to many poets, most of whom are known to us only by name.

Both cities were sacked several times. Timur sacked New Sarai around 1395, and Meñli I Giray of the Crimean Khanate sacked New Sarai around 1502. The forces of Ivan the Terrible finally destroyed Sarai after conquering the Astrakhan Khanate in 1556.

In 1623-1624, a Russian merchant, Fedot Kotov, travelled to Persia via the lower Volga. He described the site of Sarai:

Here by the river Akhtuba stands the Golden Horde. The khan’s court, palaces, and courts, and mosques are all made of stone. But now all these buildings are being dismantled and the stone is being taken to Astrakhan.

The Golden Horde (Mongolian: Altan Ord; Russian: Zolotaya Orda; Tatar: Altın Urda) was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire after 1259 it became a functionally separate khanate.

After the death of Batu Khan (the founder of the Golden Horde) in 1255, his dynasty flourished for a full century, until 1359. The Horde’s military power peaked during the reign of Uzbeg (1312–1341), who adopted Islam. The territory of the Golden Horde at its peak included most of Eastern Europe from the Urals to the Danube River, and extended east deep into Siberia. In the south, the Golden Horde’s lands bordered on the Black Sea, the Caucasus Mountains, and the territories of the Mongol dynasty known as the Ilkhanate.

The khanate experienced violent internal political disorder beginning in 1359, before it briefly reunited (1381–1395) under Tokhtamysh. However, soon after the 1396 invasion of Timur, the founder of the Timurid Empire, the Golden Horde broke into smaller Tatar khanates which declined steadily in power. At the start of the 15th century, the Horde began to fall apart. By 1466, it was being referred to simply as the “Great Horde”. Within its territories there emerged numerous predominantly Turkic-speaking khanates. These internal struggles allowed the northern vassal state of Muscovy to rid itself of the “Tatar Yoke” at the Great stand on the Ugra river in 1480. The Crimean Khanate and the Kazakh Khanate, the last remnants of the Golden Horde, survived until 1783 and 1847 respectively.

Leaving Russia and entering Kazakhstan was typically time-consuming and bureaucratic including acquiring and submitting “tallons”, one of which was momentarily lost, although everyone was friendly. The road was appalling, and we followed a Turkish truck for the first 25 miles which took two and a half hours. The road got better after passing a small town and was metalled although full of potholes, some of which were large enough to swallow the van. Eventually we found a filling station and spent the night parked outside it.