RHUDDLAN

On the way from Alrewas to Conwy we stopped at Rhuddlan to look at the castle, but only from a distance as it was closed for winter. Begun in 1277 by Edward I it was the first of the revolutionary concentric, or ‘walls within walls’, castles designed by master architect James of St George.

Most impressive was the inner diamond-shaped stronghold with its twin-towered gatehouses. This sat inside a ring of lower turreted walls. Further beyond was a deep dry moat linked to the River Clwyd, the route of which had been changed so that it could supply the castle from the river.

CONWY

We arrived at the Morfa Bach car park in the evening and wandered round a virtually deserted town looking for somewhere to eat. We eventually found the Castle Hotel where we had an excellent meal. After spending the night in the car park for 80 p I paid for 4 hours by card and then got a £50 fine for not displaying a non-existent ticket.

In the meantime we walked the town walls and then visited the castle. Having joined Cadw we got in for free and saved £22. The castle was built in 1283-1287 during Edward 1’s conquest of Wales. It withstood the siege of Madog ap Llywelyn in the winter of 1294–95, acted as a temporary haven for Richard II in 1399 and was held for several months by forces loyal to Owain Glyndwr in 1401. Following the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, the castle was held by forces loyal to Charles I, holding out until 1646 when it surrendered to the Parliamentary armies. In the aftermath, the castle was partially destroyed by Parliament to prevent it being used in any further revolt, and was finally completely ruined in 1665 when its remaining iron and lead was stripped and sold off. In keeping with other Edwardian castles in North Wales, the architecture of Conwy has close links to that found in the Kingdom of Savoy during the same period, an influence probably derived from the Savoy origins of the main architect, James of Saint George.

On returning to the car park I had a debate with folks at Conwy Council and got the parking ticket cancelled as well as a promise to repay me £4.20 after the online system charged me £7.50 instead of the advertised £3.30.

Supposedly the smallest house in Britain

Jennifer walking the walls of Conwy old town

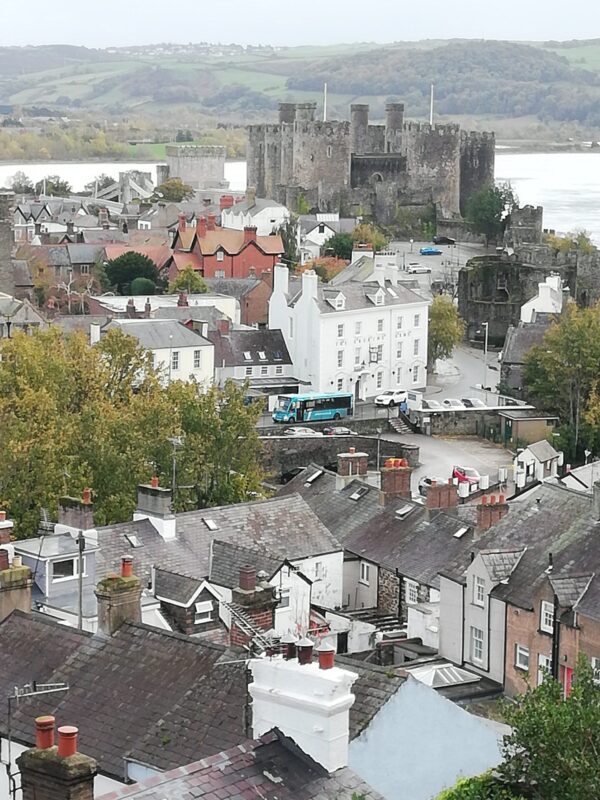

The castle from the walls

The castle from one of the towers

BEAUMARIS

We then drove to Beaumaris Castle across the Menai Straits, not across the Menai Bridge because it was closed, but across the Pont Britannia and through the village of Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch, which means ‘St Mary’s Church in the Hollow of the White Hazel Near to the Rapid Whirlpool of Llantysilio of the Red Cave’, We parked in a car park outside the castle and went into town to eat at the Dockshack chip shop. We had just about the worst meal ever and both got a slight attack of the shits.

The next day we went to look at the castle, where there isn’t a lot to see because it was never finished. Cadw says that “Beaumaris is famous as the greatest castle never built. It was the last of the royal strongholds created by Edward I in Wales – and perhaps his masterpiece. Here Edward and his architect James of St George took full advantage of a blank canvas: the ‘beau mareys’ or ‘beautiful marsh’ beside the Menai Strait. By now they had already constructed the great castles of Conwy, Caernarfon and Harlech. This was to be their crowning glory, the castle to end all castles.

The result was a fortress of immense size and near-perfect symmetry. No fewer than four concentric rings of formidable defences included a water-filled moat with its very own dock. The outer walls alone bristled with 300 arrow loops.

But lack of money and trouble brewing in Scotland meant building work had petered out by the 1320s. The south gatehouse and the six great towers in the inner ward never reached their intended height. The Llanfaes gate was barely started before being abandoned.

Beaumaris castle

Castle walls

A gargoyle on a tower

Said to be one of the oldest houses in Britain. Beaumaris

CAERNARFON

Caernarfon castle: Cadw says that “This fortress-palace on the banks of the River Seiont is grouped with Edward I’s other castles at Conwy, Beaumaris and Harlech as a World Heritage Site. But for sheer scale and architectural drama Caernarfon stands alone”.

Here Edward and his military architect Master James of St George erected a castle, town walls and a quay all at the same time. This gigantic building project eventually took 47 years and cost a staggering £25,000.

The castle was born out of bitter war with Welsh princes. So of course its immense curtain walls and daunting King’s Gate were designed to withstand assault. But the polygonal towers, eagle statues and multi-coloured masonry sent a more subtle message.

These echoed imperial Roman architecture, especially the walls of Constantinople. They also recalled the Welsh myth of Macsen Wledig, who dreamed of a great fort at the mouth of a river – ‘the fairest that man ever saw’.

Caernarfon town wall

The bay from one of the towers

Inside the castle

We drove to Llanberis where I hoped to dine at the prestigious “Petes Eats” where all the climbers eat, but it was closed. So I had one of the best fish and chips meals for an unbelievable £5.95 at the Allports fish and chip shop in the High Street. We slept in a little layby at the side of the road south of the town on the way to Llanberis Pass.

DOLBADARN

The next day we drove back to Llanberis to look at the Dolbadarn Castle, a short walk through a wood from thr road to Dinorwig hydro electric station. Occupying a lofty, lonely spot overlooking the waters of Llyn Padarn, native-built Dolbadarn Castle was once a vital link in the defences of the ancient kingdom of Gwynedd. Most likely constructed by Llywelyn ap Iorwerth (Llywelyn the Great) in the late 12th or early 13th century, it stood watch over the strategic route inland from Caernarfon to the upper Conwy Valley.

Today the site is dominated by the sturdy round tower, very different in style to the unmortared slate slabs which make up the castle’s curtain walls. Standing 50ft high, the tower’s design was probably inspired by that of similar fortresses built by Llywelyn’s rivals in the borderlands of the southern Marches.

Dolbadarn castle

Llanberis slate quarry from the castle

The outer walls of the castle

DOLWYDDLAN

A drive of 23 miles through the glorious (if we could have seen it through the rain and mist) countryside of Snowdonia via Betwys-e-Coad took us to Dolwyddlan castle. It is reached by a long path through a farmyard and its position on the top of a hill meant that it was very windy when I went (Jennifer stayed in the van having seen it many times).

One of a group of fortresses built to command the mountain passes, it stands as a lasting memorial to Prince Llywelyn ap Iorwerth. He was the undisputed ruler of Gwynedd from 1201 to his death in 1240.

But Dolwyddelan was finally conquered during the reign of his grandson Llywelyn ap Gruffudd by the English king Edward I. It marked a crucial stage in his relentless campaign to crush the Welsh once and for all.

Edward set his own stamp on Dolwyddelan from the day it fell in 1283. The garrison was hastily equipped with camouflage white tunics – perfect for winter warfare in the mountains. He raised the height of the keep, built a new tower and installed a siege engine complete with stone ‘cannon balls’.

Nothing lasts for ever. By the early 19th century Dolwyddelan was a romantic ruin popular with landscape artists. Then Lord Willoughby de Eresby decided to ‘restore’ the keep with medieval-style battlements.

You can still clearly see the join between his fantasy architecture and the genuine handiwork of Llywelyn the Great underneath.

The castle

The hillside where Llywellyn ap Iorweth was said to have been born

Harlech

We then continued for 19 miles to Harlech through Blaenau Ffestiniog and I had a look round the castle while Jennifer (still suffering the after-effects of the Beauaris fish and chips) stayed in the van.

Cadw says that Harlech Castle crowns a sheer rocky crag overlooking the dunes far below, the rugged peaks of Snowdonia rising as a backdrop. Against fierce competition from Conwy, Caernarfon and Beaumaris, this is probably the most spectacular setting for any of Edward I’s castles in North Wales.

Harlech was completed from ground to battlements in just seven years under the guidance of gifted architect Master James of St George. Its classic ‘walls within walls’ design makes the most of daunting natural defences.

Even when completely cut off by the rebellion of Madog ap Llywelyn the castle held out – thanks to the ‘Way from the Sea’. This path of 108 steps rising steeply up the rock face allowed the besieged defenders to be fed and watered by ship.

An incredible ‘floating’ footbridge allows you to enter this great castle as Master James intended – for the first time in 600 years.

Wikipedia says that “Harlech Castle is built onto a rocky knoll close to the Irish Sea. It was built by Edward I during his invasion of Wales between 1282 and 1289 at the relatively modest cost of £8,190. Over the next few centuries, the castle played an important part in several wars, withstanding the siege of Madog ap Llywelyn between 1294 and 1295, but falling to Prince Owain Glyndwr in 1404. It then became Glyndŵr’s residence and military headquarters for the remainder of the uprising until being recaptured by English forces in 1409. During the 15th century Wars of the Roses, Harlech was held by the Lancastians for seven years, before Yorkist troops forced its surrender in 1468, a siege memorialised in the song “Men of Harlech“. Following the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642, the castle was held by forces loyal to Charles I, holding out until 1647 when it became the last fortification to surrender to the Parliamentary armies.

The fortification is built of local stone and concentric in design, featuring a massive gatehouse that probably once provided high-status accommodation for the castle constable and visiting dignitaries. The sea originally came much closer to Harlech than in modern times, and a water-gate and a long flight of steps leads down from the castle to the former shore, which allowed the castle to be resupplied by sea during sieges. In keeping with Edward’s other castles in the north of Wales, the architecture of Harlech has close links to that found in the County of Savoy during the same period, an influence probably derived from the Savoy origins of the main architect, James of Saint George

Entrance to the castle

From the top of a tower

Seaward entrance to the castle

Inside the castle

Criccieth

We then drove to Criccieth for our last castle and slept in a car park overlooking the town. Cadw says that “Crowning its own rocky headland between two beaches it commands astonishing views over the town and across the wide sweep of Cardigan Bay.

No wonder Turner felt moved to paint it. By then it was a picturesque ruin – destroyed by one of Wales’s most powerful medieval princes, Owain Glyndŵr.

But it was built by two of his illustrious predecessors. First Llywelyn ap Iorwerth created the immense gatehouse flanked by D-shaped stone towers. Then his grandson Llywelyn ap Gruffudd – or Llywelyn the Last – added the outer ward, curtain walls and two new towers.

Still this craggy fortress wasn’t enough to withstand the invasion of Edward I. The English king made a few improvements of his own, equipping the north tower with a stone-throwing machine to deter Welsh attacks. It was still in English hands in 1404 when the towers were burnt red by Owain Glyndŵr. Without a garrison to protect it, the town became entirely Welsh once more.

A motte and bailey stood at a different site in Criccieth before the masonry castle was built. In 1239, Llywelyn the Great imprisoned Gruffudd ap Llywelyn ap Iorwerth and Owain Goch, respectively his son and grandson, at Criccieth; this was likely at the castle.

In 1283 the castle was captured by English under the command of Edward I. It was then remodelled by James of St George.

In 1294, Madoc ap Llywelyn, a distant relation of Llywelyn ap Gruffud, began an uprising against English rule that spread quickly through Wales. Several English-held towns were razed and Criccieth (along with Harlech Castle and Aberystwyth Castle) were besieged that winter. Its residents survived until spring when the castle was resupplied.

In the 14th century the castle had a notable Welsh constable called Hywel ap Gruffydd, known as Howell the Axe, who fought for Edward III at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356.

The castle was used as a prison until 1404 when Welsh forces captured the castle during the rebellion of Owain Glyndwr. The Welsh then tore down its walls and set the castle alight. Some stonework still shows the scorch marks. Around that time it was noted that “Crukkith Castle had Roger de Accon for Constable, with six men-at-arms and fifty archers; annual maintenance £416, 14s, 2d.”

After looking round the castle we then drove back to Harlech because Jennifer wanted to look round it, and then wet home

Criccieth seafront

Rough seas at Criccieth

The castle from the road

Jennifer at Criccieth

Inside the castle

Entrance to the castle