30th October (Saturday) Stornoway to Perth

We spent Saturday night in our van in the ferry car park, trying to sleep despite a refrigeration lorry constantly revving up its engine. The journeys on the ferry to Ullapool and the bus from Ullapool to Inverness were uneventful. Jennifer had booked a cheap train journey to Glasgow and the aim was to stay overnight in Glasgow before continuing to Prestwick the next day. We had forgotten about COP-26 until we discovered that every single hotel and B&B in Glasgow were fully booked. So we decided to get off the train at Perth, having booked the West Lea guesthouse for £70. It was good value with a comfortable room although the breakfast could have been bigger. The owner was very helpful in printing off our Passenger Locator Forms (PLFs) and check-ins. We had an excellent meal at The Tavern for a reasonable price. Filling in the Passenger Locator Form was a doddle, but there was a problem over Jennifer’s check-in. It kept telling me that her name and flight reservation weren’t recognised. I spent 3 hours on Ryanair’s chat thingy but were eventually told that nothing could be done. One last desperate attempt and, somehow or other, it worked. Ryanair charge you £55 if you check-in at the airport!!!

31st October (Sunday). Perth to Fuengirola

We got the Megabus from Broxden to Glasgow, and the price is supposed to include a free bus ride from central Perth to Broxden. However, it being Sunday, we had to get a taxi to Broxden which cost more than the bus to Glasgow. We then got a bus from Glasgow to Prestwick airport, which was like a morgue. We were the only passengers there, together with 100 policemen (yes 100, that’s what they told us, although they didn’t know why). Eventually an airport employee told me that Joe Biden might be coming through. Nothing was open (the police had their own facilities) so we had to get a cup of dishwater from a machine. The flight was typical Ryanair, with extra payments for insurance, seat location, baggage etc (we didn’t pay for any of that bollox) although they charged us an extra £9 for the privilege of not being charged an extra £29 for something which I couldn’t find out what it was. The flight to Malaga airport was comfortable and, because the plane was only part-full Jennifer was able to come and sit next to me.

We hired a car from RecordGo; the car hire for 14 days was 250 euros and the insurance was 264 euros! That was for a Fiat 500, but they hadn’t got one left so we got a much bigger Toyota Aigoe for the same price. Driving out of Malaga was easy enough but the information sheet from Club La Costa told us we had to take a right turn somewhere which I did too early so, instead of a straight run for 30 minutes, we spent 3 hours fighting our way through shit-holes like Torremolinos and Benalmedina and went for miles up a tortuous route into the mountains to Mijas before I found a place to turn round and get back to the main AP-7 road. Club La Costa is a huge site and their sign posts are very small and impossible to read in the dark. We must have spent two hours cruising around before we found a reception place bathed in light so I asked Jennifer to go and ask where the Santa Cruz Suite was; by a coincidence we were there. Our apartment had an enormous jacuzzi. Our friends Phil an Sue were already there, having got there with no problems.

1st November (Monday)

mde

Monday was a lazy day. I went for a short walk following the site map and found a small restaurant with a grumpy looking woman standing outside. Didn’t go in. In the evening we went to a restaurant on the beach through a storm tunnel which passed under the motorway. It was rather expensive with a plate of paella costing 18 euros. I had the more expensive version at 21 euros with prawns that the chef had de-shelled, so I didn’t have to get my fingers covered in grease. It was very nice with plenty of large prawns. A vast improvement on the crappy paella we had in Sevilla four years ago which had a small number of tiny prawns.

2nd November (Tuesday)

On Tuesday we went to Marbella to see Nick and Katherine. They actually live at Nagueles on the western edge of Marbella (overlooked by the La Concha mountain with a height of 3,986 feet) and it was a walk of about 1.5 miles into the centre of the town, which was more interesting than I expected. Marbella is described in the tourist blurb as a “quality resort”, which means that its a cut above the likes of Torremolinas. It just means that the horrible seafront blocks of apartments are marginally less horrible (and astronomically more expensive) than the seafront apartments of Torremolinas. And the tourists are somewhat more upper-class and gentile than the yobs and piss-heads elsewhere on the Costa Del Sol. There is a rather nice traffic-free (apart from bicycles) walk all the way along the seafront.

The old town (casco antiguo) is rather charming with whitewashed alleyways and beautiful flowers in green pots stuck to the walls. The centre of the town is the Plaza de los Naranjos (Square of Oranges) which, unsurprisingly, is full of orange trees. It is spoilt by being almost entirely covered by the dining areas of the surrounding restaurants, and by some hideous modern-art contraptions. During Moorish times, the area was a maze of narrow streets like the old town of Marrakesh, but they were bulldozed in the 1490’s to create the sort of square which characterised every Christian town. The Ayuntamiento (Town Hall) is located next to the tourist office and was built by Ferdinand & Isabella when they conquered Marbella from the Moors without bloodshed in 1485. There is a fountain in the middle constructed by the town’s first Christian mayor in 1504.

The Romans had a settlement at Marbella although nothing remains apart from some ionic capitals (tops of columns on which the ceiling rests) which are incorporated in the walls of the Moorish Alcazaba (fortress). We kept seeing fragments of the walls as we walked through the casco antigua.

Marbella became a tourist destination in the 1920’s when hotels including the Miramar were built, but tourism really took off after 1945 and Marbella became a destination for famous political and playboy personalities such as Osama bin Laden (who visited the town on a number of occasions between 1977 and 1988) and, more recently, Boris Johnson who stayed earlier this year at the £15 million mansion of his friend Zac Goldsmith.

We drove to Marbella with Phil and Sue and, after parking the car in the Mercado Municipal underground car park, we met with Nick & Katherine and had lunch at a very pleasant tapas bar in Plaza Puente Ronda in the old town. We then walked down to the shore through the Plaza de los Oranjos and the small Parque de la Alameda which has a historic fountain built in 1792. From here the Avenid del Mar connects the old town with the beach. It has a collection of 10 sculptures by Salvador Dali; they are: Naked woman climbing a staircase; Horse with people stumbling; Mercury; Perseus; Don Quixote seated; Gala gravid; Gala at the window; Trajan on horseback; Cosmic Man on dolphin and elephant.

Seafront at Marbella. African geezers selling tatty handbags. I never saw one being sold.

3rd November, Wednesday

Jennifer and I went on a short trip up into the mountains on Wednesday after going into Fuengirola to get my glasses mended at a cost of 1 euro. From there we drove due north out of the town on the road to Mijas, stopping for a sandwich at a layby on the rod which zigzagged its way upwards. For some inexplicable reason we didn’t stop at Mijas which is apparently the most interesting locality on the route. We continued to Alhaurin el Grande and stopped to walk to a castle, but it seemed too far. Castillo de la Mota looks like an ancient Moorish fortress but isn’t; a tripadvisor review indicates why I’m glad we didn’t spend time and effort going. “This could be an incredibly attractive place… It’s not a historical site, it’s less than 30 years old and only a fragment of a huge project that was abandoned soon after it began. It included another four castles of this kind, a huge golf course, gardens, a residential area, a shopping centre and god knows what else. The ruin is pretty but it’s abandoned, in terrible condition, and what’s more, it’s incredibly dangerous. Some scary drops with no railings, lots of holes, broken steps, at least 10 chances to break a leg and another 10 to kill yourself. You cannot drive to the castle, you’ll have to leave your car somewhere on the road/ path up (terrible too) and then climb up the last 300 metres, very stony and slippery. If you manage to get up there and climb to the top of the ruin, the view is wonderful. Be very very careful!”

Alhaurin el Grande (Alhaurin is a Moorish name meaning Garden of Allah) is a rather pretty little whitewashed town of narrow streets and cobbled streets. We stopped for a short walk up to the Santa Vera Cruz Chapel which was built in 1921 on the site of a 16th century chapel destroyed by Napoleon’s troops in 1812 during the four years of French occupation. The square in front has some Roman columns which have been repaired with concrete rather badly. Took a pic of a sign saying “Your dog, your responsibility” with a graphic illustration of what its about.

We then drove through Coin which is a rather boring town: Tripadvisor’s best suggestion is local hiking trails, and the second is a shopping mall. We didn’t stop. The road down to Marbella zigzags down the mountain; it was heavily trafficked and wasn’t much fun.

4th November, Thursday

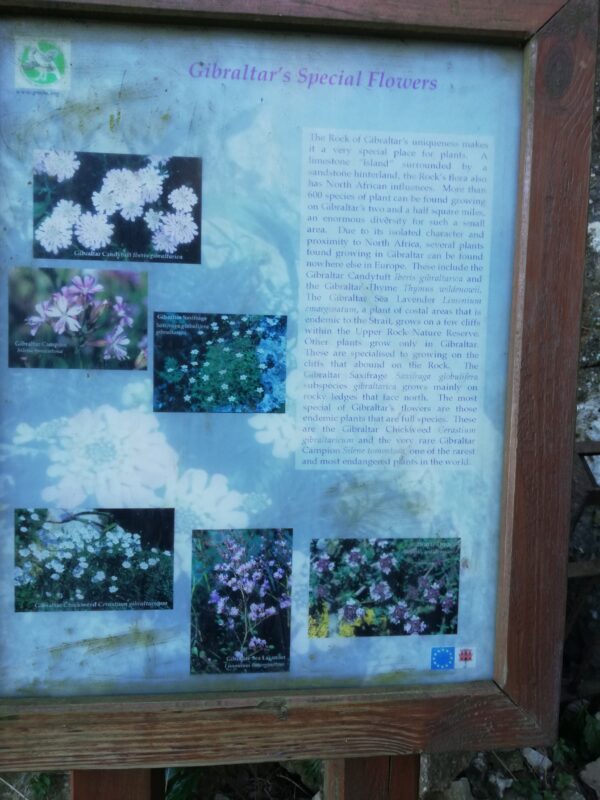

On Thursday, we all drove in Sue’s car to Marbella and dropped Jennifer at Nick’s apartment so she could spend the day with them. Sue drove us to Gibraltar, 47 miles to the south west. There was a long queue waiting to cross the frontier where we had to show our passports and inoculation certificates. The satnav took us to the entrance to the Nature Reserve where we had to turn round and park some way down the winding road which leads up to the reserve. You can only enter (through the Jews Gate) on foot unless you pay through the nose for a taxi, so we paid £13 each (Gibraltar uses both sterling and euros) and I decided to walk up the Mediterranean Steps (which I did 4 years ago) while Phil and Sue took a more leisurely walk to St Michaels Cave.

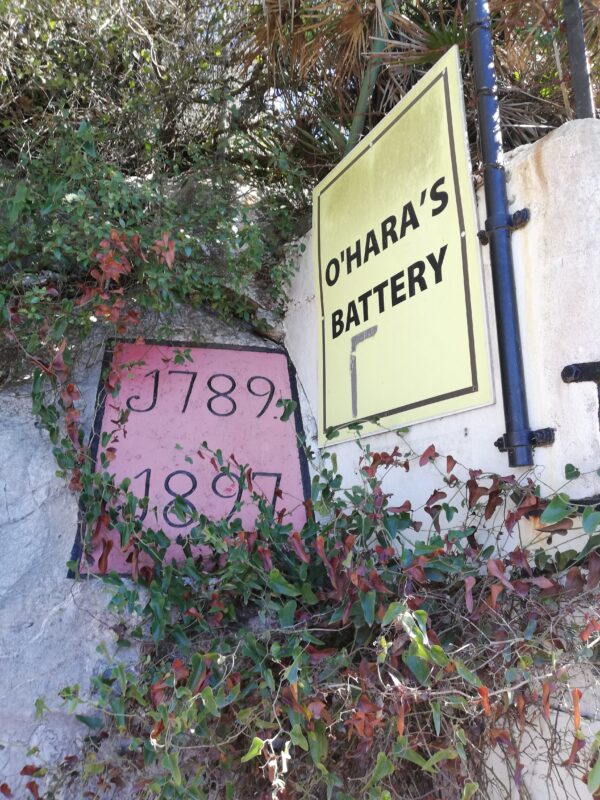

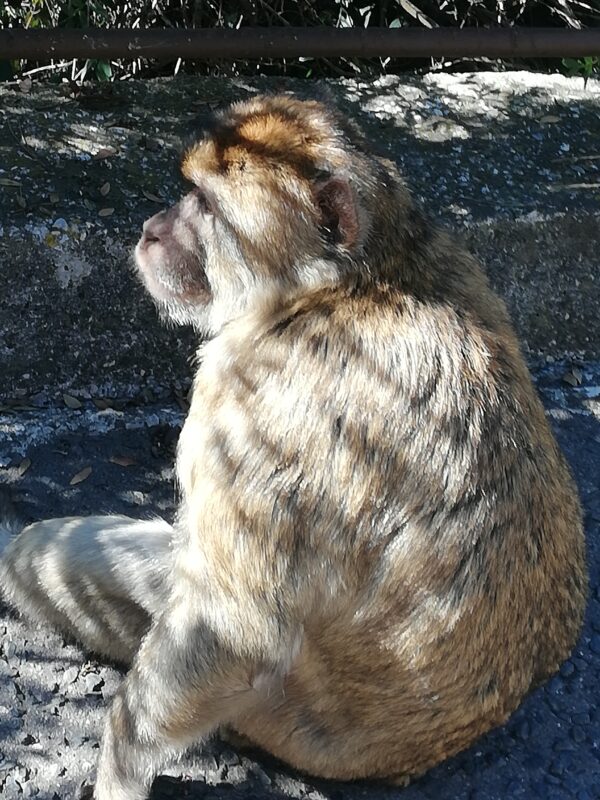

The Mediterranean Steps are spectacular: strenuous in places but not difficult. Located in the south of the Rock, the walk gives fantastic views across the Straits of Gibraltar to Morocco. The Steps culminate at a height of 1,383 feet at O’Haras Battery, a massive gun pointing across the Straits. It weighs 204 tons and has a range of 29,600 yards while distance across the Straits is 25,500 yards. The calibre is 9.2 inches and the gun fires shells weighing 380 lbs with a charge of 109 lbs. On the way down I passed St Michaels Cave but didn’t have enough time to go inside. Saw plenty of Barbary Apes which are very tame and come right up to you. There are notices warning that they are liable to snatch your phone and smash it up, and could bite if you try to touch them.

We eventually found a place to park the car (very difficult in Gib, plenty of car parks but all either full or reserved for residents) at the side of the road where we told the parking meter was bust and had a happy time walking up and down Main Street which is the main shopping area. We stopped for a meal at the Angry Friar in Main Street, where I went 4 years ago with Jennifer and recall having a decent meal. This time the chicken and mushroom pies were undercooked but tasty enough and moderately priced. Interestingly we were told by the owner that the card reader was bust and we would have to pay in cash, the assumption being that, having come from Spain, we would have only euros. When we got the bill, I was amazed to see that the exchange rate was 1.5 E to the £ rather than 1.17, which means that we would have been over charged by 28%. Sue went off to get some sterling from an ATM and met a friendly Gibraltarian who told her that many Gib cafes and shops pull the same scam to screw money out of tourists. Then we went home.

5th November Friday

Drove to Marbella and went to a tapas bar with Nick and Katherine. Tapas are small plates of bite-sized food in a wide variety of types. You normally get 6 for 10 E which amounts to a decent size meal. The tapa is derived from the Spanish verb “taper” to cover because, in the good old days, the places serving sherry used to provide thin slices of chorizo or ham to cover the glass between sips so the fruit flies couldn’t get at the sherry. The tapas tradition began when king Alfonso X of Castile (1252-1284) recovered from an illness by drinking wine with small dishes between meals. After regaining his health, the king ordered that taverns would not be allowed to serve wine to customers unless it was accompanied by a small snack or “tapa”. Another popular explanation says that King Alfonso XIII (1886-1931) stopped by a famous tavern in Cadiz where he ordered a cup of wine. The waiter covered the glass with a slice of cured ham before offering it to the king, to protect the wine from the beach sand, as Cádiz is a windy place. The king, after drinking the wine and eating the tapa, ordered another wine “with the cover”.

In the afternoon, I walked from CLC, past the massive sign, to Fuengirola as far as the rough stone jetty extending into the sea. Some poor girl was crying hysterically into her phone and, assuming her Spanish jigolo had dumped her, I told her “Never mind, play your cards right you might get off with me”. She stopped crying and smiled. My good deed for the day, until she started crying again. The first time I travelled down this coast in 1968, it consisted of small villages made of whitewashed mudbrick buildings with flat roofs (and sometimes donkeys feeding on them), cobbled streets smelling of donkey shit, open sewers and the smell of piss wherever you went. Very few cars but enough lorries for you to get places with jolly Spanish drivers able to have quite a good conversation in sign language. My sort of place, as Boris said about Peppa Pig World.

The pic of Fuengirola’s castle is taken from a bridge crossing a weird river which gets to about 20 feet of the sea then stops, and a bloke in a little digger seems to have a full time job of deepening the last 20 feet to let the water out. Castillo Sohail was built in AD 956 by Abd-ar-Rahman III to strengthen the coastal defences. He was the Caligh of Cordoba from 929 o 961 and his rule is noted for its religious tolerance. In 2000 the Town of Fuengirola renovated the ruins of the castle turning it into a tourist attraction and functioning space used for concerts and other festivals. Excavated stone ruins on public display at the western base of the hill on which the castle sits are dated back to before the Roman Republic occupied Fuengirola at least 300 BC. I didn’t bother climbing the hill to look at the castle because Phil had told me there was nothing to see.

6th November Saturday

We went to Marbella to pick up Nick, Katherine and Lily and brought them back to spend the weekend with us. In the evening we took the little train that drives round the CLC site to Restaurante el Tajo where we had a reasonably cooked meal but rather small portions. Most Tripadvisor people give it 5 stars, so perhaps it is one of these “fine dining” places where you get small helpings on big plates. Seems all the other diners were English including some old bat who kept saying “grassyarse”to the waiter. I suppose she meant “grathias” (spelt “gracias”) which means “thankyou”.

7th November Sunday

Nick told us that entry to the museums at Malaga are free after 4 pm and I can’t resist something free, so off we went. Able to park somewhere, we made for a tapas restaurant and had an excellent meal despite a bloke playing a violin who came and stood over us wanting money until he twigged that we were British and hence didn’t have much money. One thing that struck me throughout the fortnight was the virtual absence of any British tourists, but I’ll explain one likely explanation later.

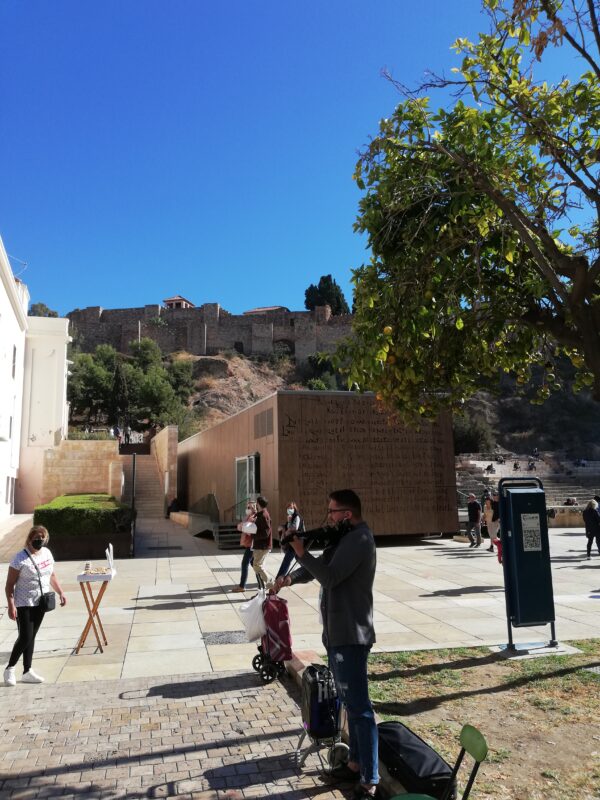

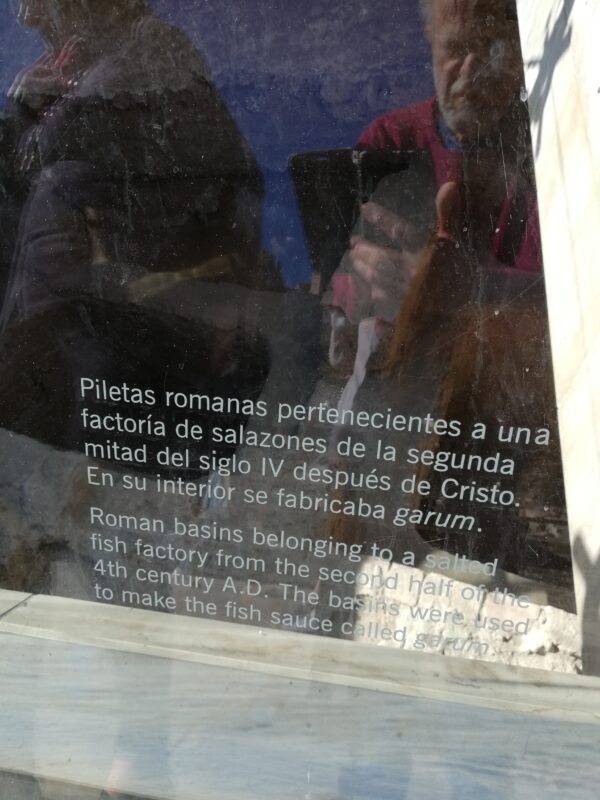

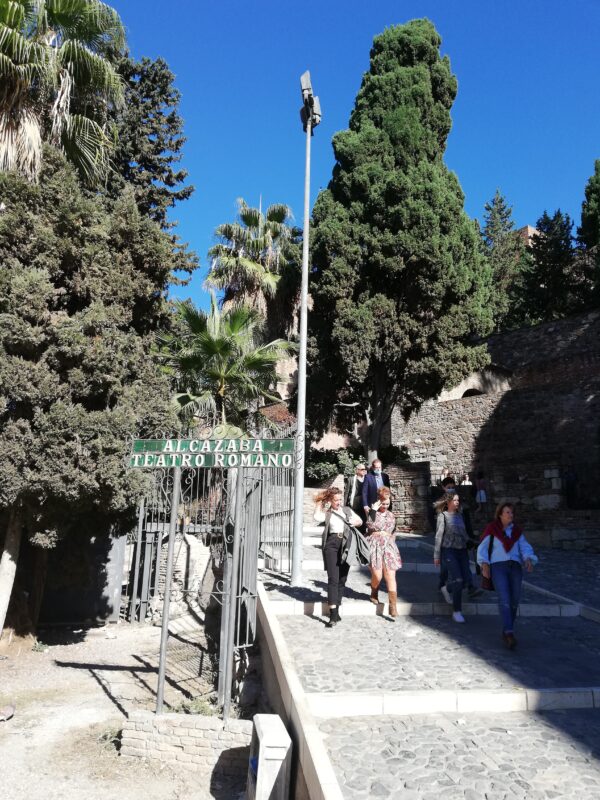

The restaurant was within sight of Malaga’s main tourist attraction, the Alcazaba, a massive fortress. It was built by the Hammudid dynasty in the early 11th century. It is the best-preserved alcazaba (from the Arabic al-qasbah meaning “citadel”) in Spain. Adjacent to the entrance of the Alcazaba are remnants of a Roman theatre dating to the 1st century BC, which are undergoing restoration. In particular, there is a glass case in the square in front of the Alcazaba containing Roman basins belonging to a salted fish factory from the second half of the 4th century AD. The basins were used to make the fish sauce called “garum”.

Some of the Roman-era materials were reused in the Moorish construction of the Alcazaba. The Alcazaba was connected by a walled corridor to the higher Castle of Gibralfaro. Ferdinand and Isabella captured Málaga from the Moors after the Siege of Malaga (1487), one of the longest sieges in the Reconquista, and raised their standard at the “Torre del Homenaje” in the inner citadel. The Alcazaba of Málaga is the prototype of military architecture in the Taifa period, with its double walls and massive entry fortifications. Its only parallel is the castle of Krak des Chevaliers in Syria.

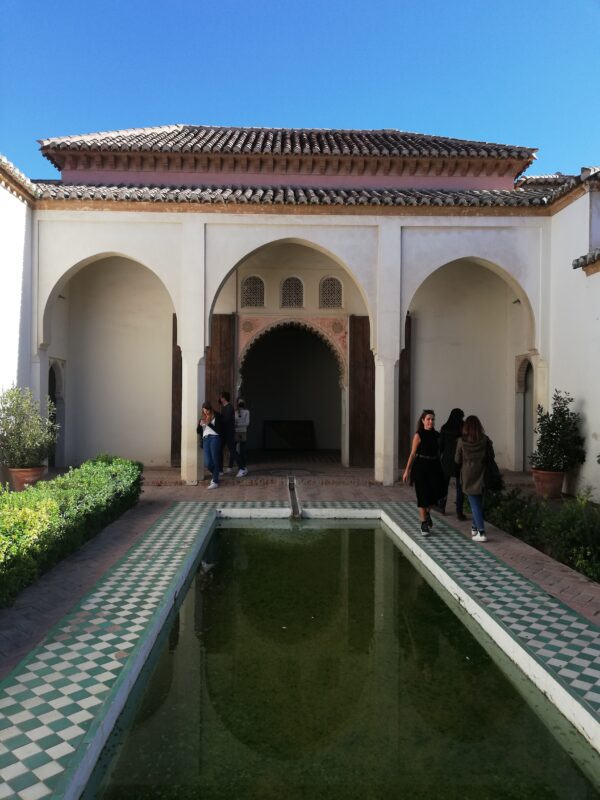

The outer citadel entrance is through a gateway called “Puerta de la Bóveda” (Vault Gate). The entrance gate doubles back on itself, a design intended to make progress difficult for attacking forces. The pathway winds up through gardens, with a number of elaborate fountains, passing the gateways of Puerta de las Columnas (Gate of the Columns), renamed Torre del Cristo (Tower of Christ), which reuses materials from the Roman ruins, and which turns at right angles to again impede the progress of attackers. The Torre del Cristo once served as a chapel. The inner enclosure can only be accessed through the Puerta de los Cuartos de Granada (Gate of the Granada Quarters) which acts as the defence for the western side of the palace. On the eastern side is the Torre del Homenaje (Tower of Tribute) which is in a semi-ruinous state.

Inside the second wall is the Palace and some other dwellings which were built on three consecutive Andalusian patios during the 11th, 13th and 14th centuries. They include the Cuartos de Granada (Quarters of Granada) which served as the home of the kings and governors.

The statue is of Solomon ibn Gabirol. Otherwise known as Solomon ben Judah was an 11th-century Andalusian poet and Jewish philosopher in the Neo-Platonic tradition. He published over a hundred poems, as well as works of biblical exegesis, philosophy, ethics, and satire. One source credits ibn Gabirol with creating a golem, possibly female, for household chores. In the 19th century it was discovered that medieval translators had Latinised Gabirol’s name to Avicebron or Avencebrol and had translated his work on Jewish Neo-Platonic philosophy into a Latin form that had in the intervening centuries been highly regarded as a work of Islamic or Christian scholarship. As such, ibn Gabirol is well known in the history of philosophy for the doctrine that all things, including soul and intellect, are composed of matter and form (“Universal Hylomorphism”), and for his emphasis on divine will.

We went to the market in Plaza de la Mercad and toured the stalls, where some tourist tat was bought; I was more interested in the obelisk commemorating the men of Malaga who died fighting during the rebellions against King Ferdinand 7th in 1831. One of the most notable rebellions of the time was by General Jose Maria de Torrijos. He had spent time in London and drew support from liberals like Tennyson and Carlysle and John Sterling whose Irish cousin Lieutenant Robert Boyd had a £4,000 inheritance and funded a ship which was seized by British authorities on request of Spanish envoy in London. Sterling withdrew after suddenly becoming engaged. Undeterred revolutionaries managed to regroup in Gibraltar in 1830. They attacked San Roque, then La Linea. Coronel Salvador Manzanares, minister in the Liberal Triennium (1820-1823) lead 17 comrades from Gibraltar and landed at Babonaque, Estepona in February 1831. They were defeated and 48 men including Torrijos and Boyd were executed in Estepona on December 2nd 1831.

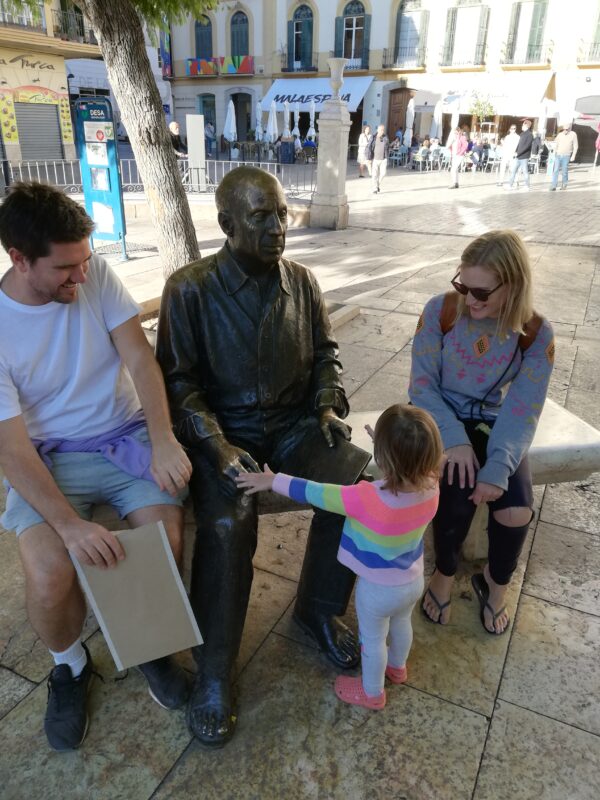

We then visited the house on one side of the Plaza de la Mercad where Picasso was born in 1881. Built in 1861, Picasso’s father, José Ruiz Blasco rented the first floor of the house from 1880 to 1883. Later they lived nearby, still in the Plaza de Merced and it was not until 1891 when Jose Ruiz is offered a job as an art teacher in La Coruña that the family moved to Galicia, where they stayed until 1895. They later moved to Barcelona until 1904 when Picasso moved to live in France. Despite the distance, Picasso was always closely related to his hometown visiting Málaga city on several occasions and recalling it in his work where his Malaga roots are perceived. But the house didn´t always have such greatness, since it was abandoned for almost a century until it was declared a national monument and began hosting the first works of the painter. At first, the building was modest, but with the help of donations from family and friends, it gradually grew until a large remodeling and expansion of the entire building was carried out in 1998.

We didn’t have time to visit the Picasso Museum for various reasons, but we did manage to pose beside the statue of Picasso outside his birth house.

8th November, Monday

On Monday, Sue drove us to Ronda along the fast road which entails driving due west to San Pedro de Alcantara just west of Marbella, and then 30 miles NNW to Ronda up a good but winding road. The road reaches a height of 3,671 feet before dropping to 2,425 ft at Ronda.

Around the city are remains of prehistoric settlements dating to the Neolithic Age, including the rock paintings of Cuelva de la Pileta. Ronda was, however, first settled by the early Celts, who called it Arunda in the sixth century BC. Later Phoenician settlers established themselves nearby to found Acinipo (sometimes referred to as Ronda la Vieja, Old Ronda). The current Ronda is of Roman origins, having been founded as a fortified post in the Second Punic War, by Scipio Africanus. Ronda received the title of city at the time of Julius Caesar.

In the fifth century AD, Ronda was conquered by the Suebi, led by Rechila, being reconquered in the following century by the Eastern Roman Empire, under whose rule Acinipo was abandoned. Later, the Visigoth king Leovigild captured the city. Ronda was part of the Visigoth realm until 713, when it fell to the Berbers, who named it Hisn Ar-Rundah (“Castle of Rundah”) and made it the capital of the Takurunna Province.

It was the hometown of the polymath Abbas ibn Firnas (810–887), an an inventor, engineer, alleged aviator, chemist, physician, Muslim poet and Andalusian musician.

After the disintegration of the caliphate of Cordoba, Ronda became the capital of a small kingdom ruled by the Berber Banu Ifran, the taifa of Ronda. During this period, Ronda gained most of its Islamic architectural heritage. In 1065, Ronda was conquered by the taifa of Seville led by Abbad II al-Mu’tadid. The poet Salih ben Sharif al-Rundi (1204–1285) and the Sufi scholar Ibn Abbad al-Rundi (1333–1390) were born in Ronda.

The Islamic domination of Ronda ended in 1485, when it was conquered by the Marquis of Cádiz after a brief siege. Subsequently, most of the city’s old edifices were renewed or adapted to Christian roles, while numerous others were built in newly created quarters such as Mercadillo and San Francisco. The Plaza de Toros de Ronda was founded in the town in 1572.

The Spanish Inquisition affected the Muslims living in Spain greatly. Shortly after 1492, when the last outpost of Muslim presence in the Iberian Peninsula, Granada, was conquered, the Spanish decreed that all Muslims must either vacate the peninsula without their belongings or convert. Many people overtly converted to keep their possessions while secretly practicing their religion. Muslims who converted were called Moriscos. They were required to wear upon their caps and turbans a blue crescent. Traveling without a permit meant a death sentence. This systematic suppression forced the Muslims to seek refuge in mountainous regions of southern Andalusia; Ronda was one such refuge.

On May 25, 1566, Phillip II decreed the use of the Arabic language (written or spoken) illegal, required that doors to homes remain open on Fridays to verify that no Muslim Friday prayers were conducted, and levied heavy taxes on Morisco trades. This led to several rebellions, one of them in Ronda under the leadership of Al-Fihrey. Al-Fihrey’s soldiers defeated the Spanish army sent to suppress them under the leadership of Alfonso de Aguilar. The massacre of the Spaniards prompted Phillip II to order the expulsion of all Moriscos in Ronda.

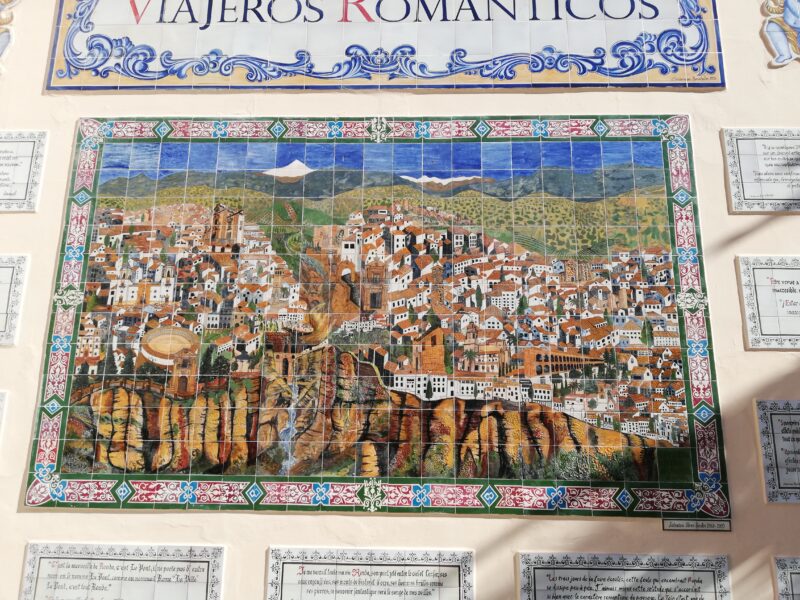

In the early 19th century, the Napoleonic invasion and the subsequent Peninsular War caused much suffering in Ronda, whose inhabitants were reduced from 15,600 to 5,000 in three years. Ronda’s area became the base first of guerrilla warriors, then of numerous bandits, whose deeds inspired artists such as Washington Irving, Prosper Merimee and Gustave Dore. In the 19th century, the economy of Ronda was mainly based on agricultural activities. In 1918, the city was the seat of the Assembly of Ronda, in which the Andalusian flag, coat of arms, and anthem were designed.

Ronda’s Romero family—from Francisco, born in 1698, to his son Juan, to his famous grandson Pedro, who died in 1839—played a principal role in the development of modern Spanish bullfighting. In a family responsible for such innovations as the use of the cape, or muleta, and a sword especially designed for the kill, Pedro in particular transformed bullfighting into “an art and a skill in its own right, and not simply … a clownishly macho preamble to the bull’s slaughter”. Ronda was heavily affected by the Spanish Civil War, which led to emigration and depopulation. The scene in chapter 10 of Hemingway’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls”, describing the 1936 execution of Fascist sympathisers in a (fictional) village who are thrown off a cliff, is considered to be modeled on actual events of the time in Ronda.

We parked the car and walked down C.Infantes (which becomes C.Padre Mariano Soubiron) to a beautiful little park overlooking the gorge of the Rio Guadelevin. There is a statue of Ernest Hemingway in the park, probably because it adjoins the Bullring of the Royal Cavalry of Ronda. We then wandered down C.Virgen de la Paz and C.Arminan across the iconic Puente Nuevo bridge over the El Tajo Gorge. It is normally photoed from the bottom of the gorge.

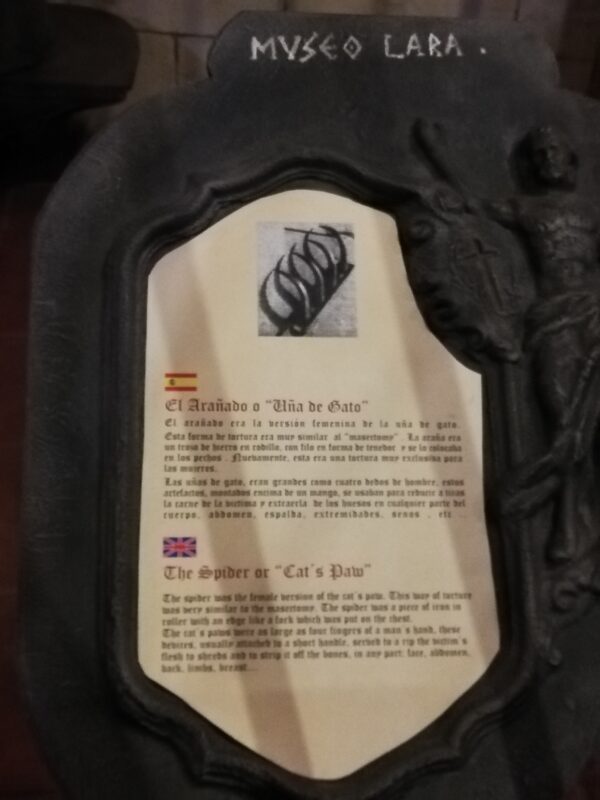

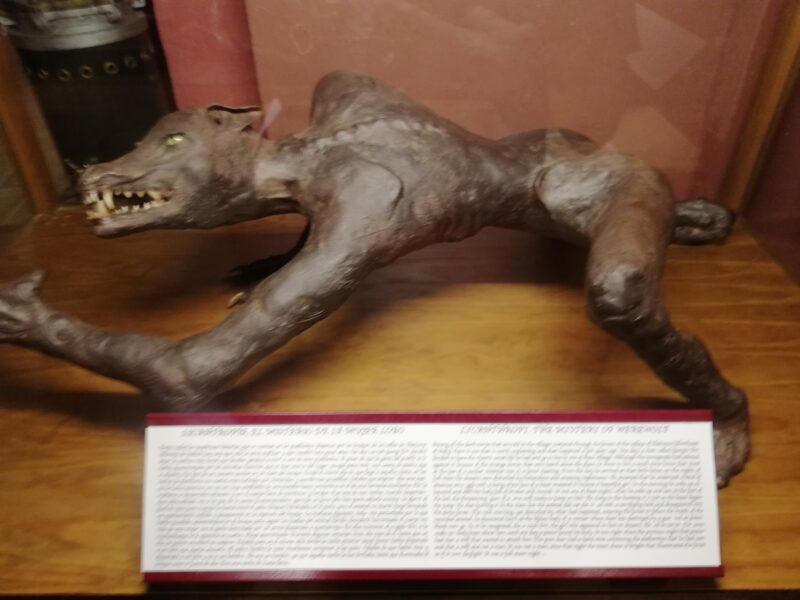

Walking to the old town,we stopped at Museo Lara which was very interesting. Being a ghoul I liked the exhibition on torture instruments of the Inquisition used on Moriscos (Moors who had been forcibly converted to Christianity but continued to practice their faith) and witches, although bruyeria (witchcraft) wasn’t considered much of crime in Spain. The museum has an iron maiden, which was created by a Nuremburg museum owner in the 1880’s and never used as such, and a genuine iron maiden, which is an iron chair covered with spikes on which the victim was seated and a number of ropes were tightened as they were impaled deeper and deeper on the spikes. If they still failed to confess then the chair was heated up until the victim began to roast, and this always got the confession. There is also a genuine cats claw consisting of 4 razor-sharp blades on the end of a stick and used to tear the victim’s flesh from his bones prior to his execution. The museum also has a headcrusher (no explanation needed) and a strapado (a sort of vertical rack). These items were discovered over the years in Germany.

We then wandered into the Plaza Duquesa de Parcent and had a very pleasant meal outside the Meson Catedral which makes pretty grim reading on Google Earth. Half the reviews were “terrible”. We thought it was quite good; probably because they weren’t overworked during the off-season. I picked up a copy of the local English paper with a rather disparaging article on the King of Spain who apparently was injected with female hormone to reduce his rampant sex drive after it was officially categorised as a “problem of state”. He is alleged to have bonked 2,000 women between 1976 and 1994. That’s one every 3 days. Even I can’t beat that. We then went for a walk round the narrow streets of the old town, and then went home.

9th November, Tuesday

Quiet day. I can’t remember what we did, apart from going to Marbella and having a very cheap, although perectly adequate, meal at the Sociedad de Pesca Deportiva de Marbella.

10th November, Wednesday

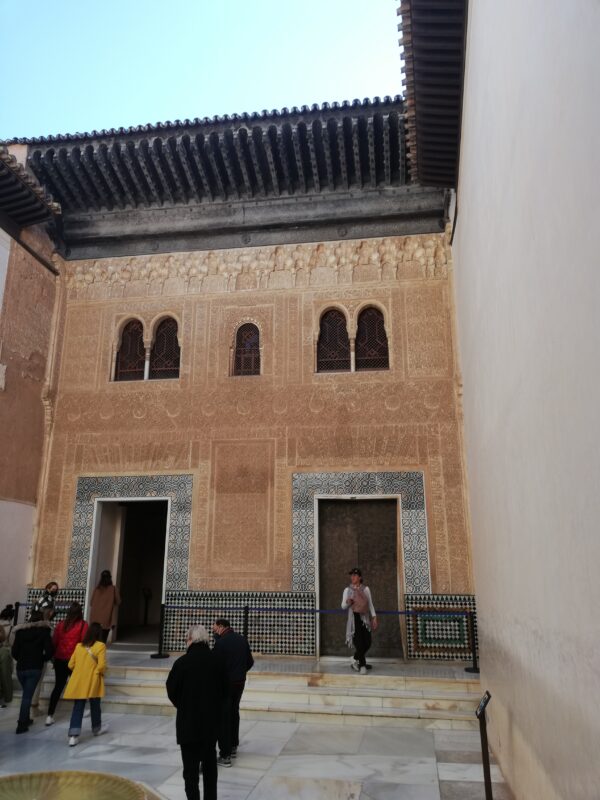

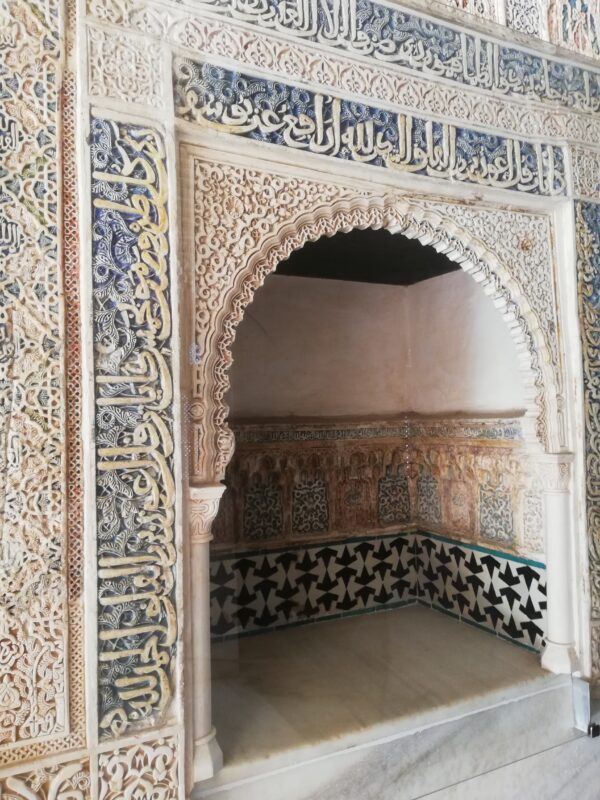

The four of us went to Granada in our car and I drove the 97 miles in 1 hour 40 minutes. We had booked to go round the Nasrid Palace for 2 pm and got to the Alhambra with plenty of time, so we visited the Generalife garden. Pictures 1 and 2 show some of the beautiful flowers which were still blooming in November while 3 shows the Water Tower from the Generalife. Pics 4 and 5 show the Palace of the Generalife at the north western end of the gardens.

We reached the queue to get into the Nasrid Palace just before 1.30 but were not allowed in until the 2 pm slot so we sat on a wall at the side of the queue and waited. Two old gits arrived at 1.30 with tickets for 1.00 pm and despite a lengthy argument they weren’t allowed in. The poor old bloke was last seen hobbling away while being belted over the head by his wife with her handbag.

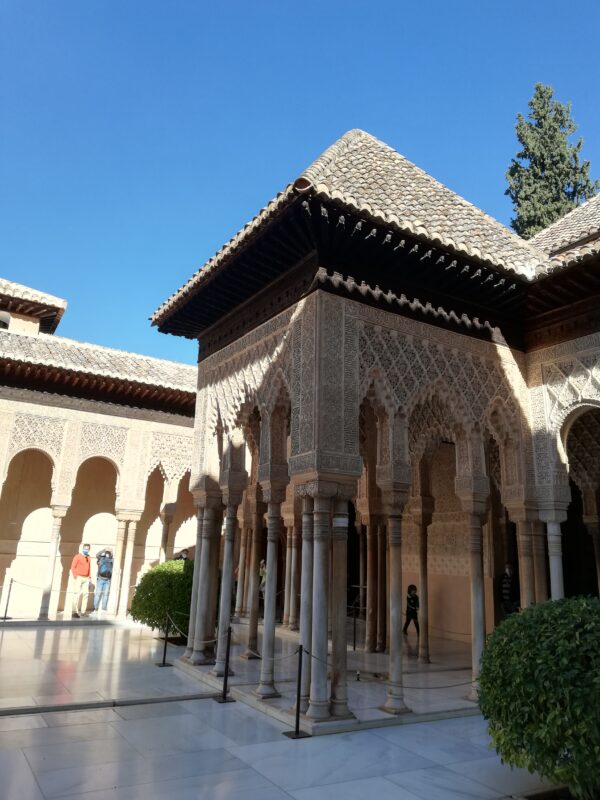

Pics 6 to 12 are of the Palace of Comares (including 11 which is the Chamber of the Ambassadors) while 13 to 18 are of the Palace of the Lions. The pic 17 is the Lindaraja Viewpoint from the Hall of the Two Sisters. Pics 19 and 20 are paintings on leather on wooden vaults in the Hall of the Kings, thought to have been painted by Christian artists while 21 is the Court of Lindaraja (part of the Christian Rooms). Pic 22 is of the Albacin area of Granada from next to the Tower of the Ladies while 23 is the Tower of the Ladies and 24 is the tower of the Pointed Battlements and 25 is Jennifer in the Lavender Garden.

The area was settled since ancient times by Iberians, Romans and Visigoths. The current settlement became a major city of Al-Andalus in the 11th century during the Zirid Taifa of Granada. In the 13th century it became the capital of the Emirate of Granada under Nasrid rule, the last Muslim-ruled state in the Iberian Peninsula. Granada was conquered in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs and progressively transformed into a Christian city over the course of the 16th century.

The Alhambra, an ancient Nasrid citadel and palace, is located in Granada. It is one of the most famous monuments of Islamic architecture and one of the most visited tourist sites in Spain. Islamic-period influence and Moorish architecture are also preserved in the Albaicín neighborhood and other medieval monuments in the city. The 16th century also saw a flourishing of Mudéjar architecture and Renaissance architecture, followed later by Baroque and Churrigueresque styles.The pomegranate (in Spanish, granada) is the heraldic device of Granada.

The Umayyad conquest of Hispania, starting in AD 711, brought large parts of the Iberian Peninsula under Moorish control and established al-Andalus. The earliest Arabic historical sources mention that a town named Qashtīliya, later known as Madīnat Ilbīra (Elvira), was located on the southern slopes of the Sierra de Elvira mountains (near present-day Atarfe), while another fortress (ḥiṣn) named Ġarnāṭa existed on the south side of the Darro River. The latter had a mainly Jewish population and thus was also known as Gharnāṭat al-Yahūd (“Gharnāṭa of the Jews”). The district around the city was known as Kūrat Ilbīra (roughly “Province of Elvira”). After 743 the town of Ilbīra was settled by soldiers from the region of Syria who played a role in supporting Abd al-Rahman I, the founder of the Emirate of Córdoba and a new Umayyad dynasty. In the late 9th century, during the reign of Abdallah (r. 844–912), the city and its surrounding district were the site of conflict between muwallads (Muslim converts) who were loyal to the central government and Arabs, led by Sawwār ibn Ḥamdūn, who resented them.

At the beginning of the 11th century, the area became dominated by the Zirids, a Sanhaja Berber group and offshoot of the Zirids who ruled parts of North Africa. This group became an important contingent in the army of ʿAbd al-Malik al-Muẓaffar, the prime minister of Caliph Hisham II (r. 976–1009) and successor to Ibn Abi ʿAmir al-Mansur (Almanzor) as de facto ruler of the Caliphate of Córdoba. For their service, the Zirids were granted control of the province of Elvira. When the Caliphate collapsed after 1009 and the Fitna (civil war) began, the Zirid leader Zawi ben Ziri established an independent kingdom for himself, the Taifa of Granada. Arab sources such as al-Idrisi consider him to be the founder of the city of Granada. His surviving memoirs – the only ones for the Spanish “Middle Ages” – provide considerable detail for this brief period. Because Madīnat Ilbīra was situated on a low plain and, as a result, difficult to protect from attacks, the ruler decided to transfer his residence to the higher situated area of Ġarnāṭa. According to Arabic sources Ilbīra was razed during the Fitna, afterwards it was not restored at its previous place and instead Ġarnāṭa, the former Jewish town, replaced it as the main city. In a short time this town was transformed into one of the most important cities of al-Andalus. Until the 11th century it had a mixed population of Christians, Muslims, and Jews.

The Zirids built their citadel and palace, known as the al-Qaṣaba al-Qadīma (“Old Citadel”), on the hill now occupied by the Albaicín neighborhood. It was connected to two smaller fortresses on the Sabika hill (site of the future Alhambra) and Mauror hill to the south. The city around it grew during the 11th century to include the Albaicín, the Sabika, the Mauror, and a part of the surrounding plains. The city was fortified with walls encompassing an area of approximately 75 hectares.The northern part of these walls, near the Albaicin citadel, have survived to the present day, along with one of its main gates, the Puerta Monaita. The now-ruined Puerta de los Tableros was built to guard the city entrance along the Darro River. The nearby Bañuelo, a former hammam (bathhouse), also likely dates from this time, as does the former minaret of a mosque in the Albaicín, now part of the Church of San José.

Under the Zirid kings Habbus ibn Maksan and Badis, the most powerful figure was the Jewish administrator known as Samuel ha-Nagid (in Hebrew) or Isma’il ibn Nagrilla (in Arabic). Samuel was a highly educated member of the former elites of Cordoba, who fled that city after the outbreak of the Fitna. He eventually found his way to Granada, where Habbus ibn Maksan appointed him his secretary in 1020 and entrusted him with many important responsibilities, including tax collection. Under Badis, he even took charge of the army. During this period, the Muslim king was looked upon as a mainly symbolic figurehead. Granada was the center of Jewish Sephardi culture and scholarship. According to Daniel Eisenberg: Early Arabic writers repeatedly called it “Garnata al-Yahud” (Granada of the Jews)…. Granada was in the eleventh century the center of Sephardic civilization at its peak, and from 1027 until 1066 Granada was a powerful Jewish state. Jews did not hold the foreigner (dhimmi) status typical of Islamic rule. Samuel ibn Nagrilla, recognized by Sephardic Jews everywhere as the quasi-political ha-Nagid (‘The Prince’), was king in all but name. As vizier he made policy and—much more unusual—led the army…. It is said that Samuel’s strengthening and fortification of Granada was what permitted it, later, to survive as the last Islamic state in the Iberian peninsula. All of the greatest figures of eleventh-century Hispano-Jewish culture are associated with Granada. Moses Ibn Ezra was from Granada; on his invitation Judah ha-Levi spent several years there as his guest. Ibn Gabirol’s patrons and hosts were the Jewish viziers of Granada, Samuel ha-Nagid and his son Joseph.

After Samuel’s death, his son Joseph took over after his position but proved to lack his father’s diplomacy, bringing on the 1066 Granada massacre, which ended the Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain.

From the late 11th century to the early 13th century, Al-Andalus was dominated by two successive North African Berber empires. The Almoravids ruled Granada from 1090 and the Almohads from 1166. Evidence from the artistic and archeological remains of this period suggest that the city thrived under the Almoravids but declined under the Almohads. Remnants of the Almohad period in the city include the Alcázar Genil, built in 1218–1219 (but later redecorated under the Nasrids), and possibly the former minaret attached to the present-day Church of San Juan de los Reyes in the Albaicin.

In 1228 Idris al-Ma’mun, the last effective Almohad ruler in al-Andalus, left the Iberian Peninsula. As Almohad rule collapsed local leaders and factions emerged across the region. With the Reconquista in full swing, the Christian kingdoms of Castile and Aragon – under kings Ferdinand III and James I, respectively – made major conquests across al-Andalus. Castile captured Cordoba in 1236 and Seville in 1248. Meanwhile, the ambitious Ibn al-Ahmar (Muhammad I) established what became the last and longest reigning Muslim dynasty in the Iberian peninsula, the Nasrids, who ruled the Emirate of Granada. On multiple occasions Ibn al-Ahmar aligned himself with Ferdinand III, eventually agreeing to become his vassal in 1246. Granada thereafter became a tributary state to the Kingdom of Castile, although this was often interrupted by wars between the two states. The political history of the emirate was turbulent and intertwined with that of its neighbours. The Nasrids sometimes provided refuge or military aid to Castilian kings and noblemen, even against other Muslim states, while in turn the Castilians provided refuge and aid to some Nasrid emirs against other Nasrid rivals. On other occasions the Nasrids attempted to leverage the aid of the North African Marinids to ward off Castile, although Marinid interventions in the Peninsula ended after Battle of Rio Salado (1340).

The population of the emirate was also swelled by Muslim refugees from the territories newly conquered by Castile and Aragon, resulting in a small yet densely-populated territory which was more uniformly Muslim and Arabic-speaking than before. The city itself expanded and new neighbourhoods grew around the Albaicín (named after refugees from Baeza) and in Antequeruela (named after refugees from Antequera after 1410). A new set of walls was constructed further north during the 13th–14th centuries, with Puerta de Elvira as its western entrance A major Muslim cemetery existed outside this gate. The city’s heart was its Great Mosque (on the site of the present-day Granada Cathedral) and the commercial district known as the qaysariyya (the Alcaicería). Next to this was the only major madrasa built in al-Andalus, the Madrasa al-Yusufiyya (known today as the Palacio de la Madraza), founded in 1349. Other monuments from this era include the al-Funduq al-Jadida (“New Inn” or caravanserai, now known as the Corral del Carbón), built in the early 14th century, the Maristan (hospital), built in 1365–1367 and demolished in 1843, and the main mosque of the Albaicín, dating from the 13th century.

When Ibn Al-Ahmar established himself in the city he moved the royal palace from the old Zirid citadel on the Albaicín hill to the Sabika hill, beginning construction on what became the present Alhambra. The Alhambra acted as a self-contained palace-city, with its own mosque, hammams, fortress, and residential quarters for workers and servants. The most celebrated palaces that survive today, such as the Comares Palace and the Palace of the Lions, generally date from the reigns of Yusuf I (r. 1333–1354) and his son Muhammad V (r. 1354–1391, with interruptions). Some smaller examples of Nasrid palace architecture in the city have survived in the Cuarto Real de Santo Domingo (late 13th century) and the Dar al-Horra (15th century).

Partly due to the heavy tributary payments to Castile, Granada’s economy specialized in the trade of high-value goods Integrated within the European mercantile network, the ports of the kingdom fostered intense trading relations with the Genoese, but also with the Catalans, and to a lesser extent, with the Venetians, the Florentines, and the Portuguese. It provided connections with Muslim and Arab trade centers, particularly for gold from sub-Saharan Africa and the Maghreb, and exported silk and dried fruits produced in the area.

Despite its frontier position, Granada was also an important Islamic intellectual and cultural center, especially in the time of Muhammad V, with figures such as Ibn Khaldun and Ibn al-Khatib serving in the Nasrid court. Ibn Battuta, a famous traveller and historian, visited the Emirate of Granada in 1350. He described it as a powerful and self-sufficient kingdom in its own right, although frequently embroiled in skirmishes with the Kingdom of Castile. In his journal, Ibn Battuta called Granada the “metropolis of Andalusia and the bride of its cities.”

On 2 January 1492, the last Muslim ruler in Iberia, Emir Muhammad XII, known as “Boabdil” to the Spanish, surrendered complete control of the Emirate of Granada to the Catholic Monarchs (Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile), after the last episode of the Granada War.

The 1492 capitulation of the Kingdom of Granada to the Catholic Monarchs is one of the most significant events in Granada’s history. It brought the demise of the last Muslim-controlled polity in the Iberian Peninsula. The terms of the surrender explicitly allowed the Muslim inhabitants, known as mudéjares, to continue unmolested in the practice of their faith and customs. This had been a traditional practice during Castilian (and Aragonese) conquests of Muslim cities since the takeover of Toledo in the 11th century. The terms of the surrender also officially offered the same protections to the Jewish inhabitants, but in spite of this the Alhambra Decree, which forced all Jews in Spain to convert or be expelled, was issued only a few months later on March 31. This move, along with the progressive erosion of other guarantees provided by the surrender treaty, raised tensions and fears within the remaining Muslim community during the 1490s. Many of the city’s affluent Muslims and its traditional ruling classes emigrated to North Africa in the early years after the conquest, but these early emigrants numbered only a few thousand, with the rest of the population unable to afford leaving. By 1499, Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros grew frustrated with the slow pace of the efforts of the first archbishop of Granada, Hernando de Talavera, to convert non-Christians and undertook a program of forced baptisms, creating the converso (convert) class for Muslims and Jews. Cisneros’s new strategy, which was a direct violation of the terms of the treaty, provoked the Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1499–1501) centered in the rural Alpujarras region southeast of the city.

The rebellion lasted until 1500, 9 years after the conquest. Upon being conquered by the Spanish, the city did not formally establish its own town council, instead, merging the “Old Christians“, and the converted morisco elites, a decision that resulted in strong factionalism from 1508 onwards. The new period also saw the creation of a number of other new institutions such as the Cathedral Cabildo, the Captaincy–General , the Royal Chapel and the Royal Chancellery. For the rest of the 16th century the Granadan ruling oligarchy featured roughly a 40% of (Jewish) conversos and about a 31% of hidalgos.

Responding to the rebellion of 1501, the Crown of Castile rescinded the Alhambra Decree treaty, and mandated that Granada’s Muslims convert or emigrate. Under the 1492 Alhambra Decree, Spain’s Jewish population, unlike the Muslims, had already been forced to convert (the so-called conversos) under threat of expulsion or even execution. Many of the elite Muslim class subsequently emigrated to North Africa The majority of the Granada’s mudéjares converted (becoming the so-called moriscos or Moorish) so that they could stay. Both populations of converts were subject to persecution, execution, or exile, and each had cells that practiced their original religion in secrecy (the so-called marranos in the case of the conversos accused of the charge of crypto-Judaism).

11th November

Jennifer and I drove to Cordoba, a distance of 119 miles which took 2 hours along an excellent fast road. On reaching Cordoba the satnav, which worked off a google map on a phone, took us round and round in a circle round the zoo until I finally switched it off and followed my instinct which took us straight to the centre.

We managed to find a space in an underground car park which was virtually impossible to drive into despite the best efforts of an attendant, Alberto, who spent about 30 minutes waving his arms about, howling with laughter and bellowing at us in Spanish. Finally managed it and then spent 30 minutes in a queue to get into the Mezquita. Jennifer asked if it was the right place and I said “Of course it is. We’ve been here before. Look there’s a park of orange trees in front of it”. So a little old lady in the queue said “No its not, the Mezquita is somewhere else with a park of orange trees in front of it”. I stood corrected. We went to the Mezquita to be told that it was siesta time and we would have to come back at 2 pm so we went to find something to eat.

Wandering through the old town we eventually came to a decent looking restaurant and sat outside. Jennifer had a coke and I asked for an orange juice from freshly squeezed oranges. So the waiter brought me a coke. I put him right and he stomped off with a rather bad grace to actually do some work by squeezing a few oranges. However my choice of meal for the first, and probably the last, time proved better than Jennifer’s. I had a Flamenquin de Cordoba, which is one of the definitive must try foods in Cordoba. Cured ham and pork loin are rolled together and deep-fried (though some recipes include other ingredients, such as cheese, in the filling). The origins of flamenquín are muddled, with some sources claiming the dish was invented in the village of Bujalance in Cordoba province, while others trace it back to Andújar in neighbouring Jaén. However, Cordoba residents are rightly proud of this popular delicacy. Food in Cordoba is somewhat different from that in the rest of Spain, perhaps because the Moorish influence is greater, and we should certainly do some more eating there when we go again.

With still some time to kill before the Mezquita opened, we then had a row about something which neither of us can remember, so we separately together (if you see what I mean) visited the underground Roman baths studiously ignoring each other. We then walked across the famous Puente de San Rafael bridge over the Guadalquivir river. There is a statue on the bridge of the Archangel Rafael who was venerated in Cordoba as a protector against plague, and many such statues were erected. It didn’t appear to have done much good: in 1488 the city had 25,000 inhabitants until the plague killed 15,000 of them.

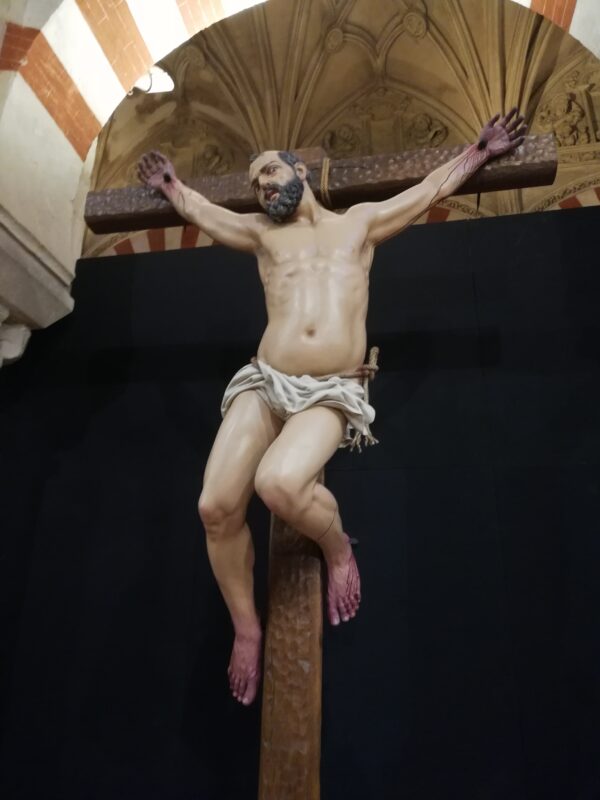

In the afternoon we visited the Mezquita and the pictures are sufficient to speak for themselves.